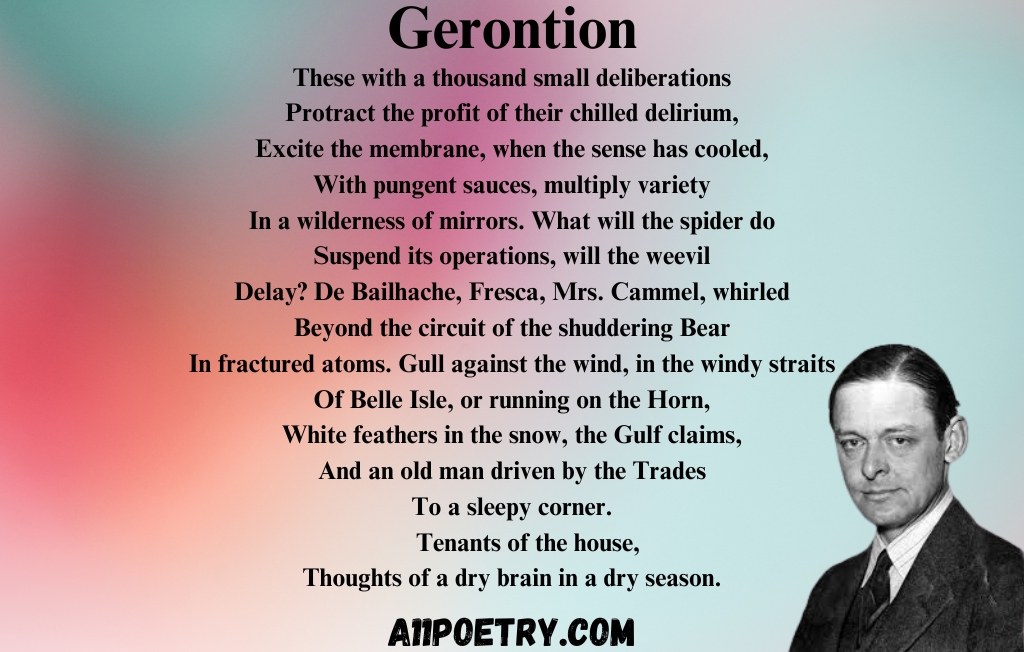

T. S. Eliot, one of the most significant figures in modernist literature, is known for his intricate poetry that explores themes of time, history, spirituality, and human frailty. Gerontion, written in 1920, is one of his most complex and introspective works. The poem is a dramatic monologue delivered by an old man who reflects on his past, the failures of history, and the decline of civilization. Through a fragmented and allusive structure, Eliot presents a haunting meditation on the modern world’s spiritual and moral disillusionment.

Background and Context

Eliot wrote Gerontion in the wake of World War I, a period marked by cultural and moral upheaval. The war had shattered the faith of many in the progress and stability of Western civilization, leaving them in search of meaning in an increasingly fragmented world. Gerontion embodies this disillusionment through a speaker who serves as both an individual voice and a symbol of the larger societal crisis.

The title Gerontion comes from the Greek word “geron,” meaning “old man.” The poem’s speaker, an elderly figure, represents a worn-out civilization reflecting on its own decline. Originally intended as a prelude to The Waste Land (1922), Gerontion shares many of the themes that Eliot would later explore more fully in his landmark work.

Summary of the Poem

The poem opens with the old man describing himself as someone who has outlived his time and is waiting for something undefined. He listens to a boy reading to him, yet he remains detached and passive:

“Here I am, an old man in a dry month,

Being read to by a boy, waiting for rain.”

This image of barrenness and stagnation sets the tone for the rest of the poem. The phrase “waiting for rain” suggests a desire for renewal, but the speaker is resigned to his desolate condition.

The poem then shifts to historical and philosophical reflections. The speaker describes history as deceptive and cyclical, filled with repeated failures and misguided ambitions:

“History has many cunning passages, contrived corridors

And issues, deceives with whispering ambitions,

Guides us by vanities.”

He sees history as a maze, leading humanity toward false hopes and inevitable disillusionment. The poem also makes frequent references to religious figures and ideas, but instead of offering hope, these references emphasize the emptiness of modern spirituality.

The final stanzas reinforce the themes of decay and regret. The speaker, who once had the potential for greatness, finds himself reduced to inaction, haunted by what he has failed to achieve. He reflects on the unfulfilled promises of the past, recognizing that his own life, like history itself, has been marked by loss and missed opportunities.

Themes in Gerontion

1. Aging and Decay

The poem is centered on an aging figure who represents both individual and societal decline. The speaker’s physical and mental frailty serve as metaphors for the moral and cultural exhaustion of Western civilization. The images of dryness and sterility throughout the poem reinforce this theme.

2. The Failure of History

Eliot portrays history as a cycle of repeated failures rather than a source of enlightenment. The speaker’s reflections reveal a deep skepticism about the idea of progress, suggesting that human ambition is often misguided and ultimately futile.

3. Spiritual Emptiness

A recurring theme in Eliot’s poetry is the loss of faith in the modern world. Gerontion is filled with religious imagery, but instead of offering redemption, these references highlight a sense of spiritual desolation. The line “After such knowledge, what forgiveness?” encapsulates the idea that awareness of human failure does not bring salvation, only deeper despair.

4. Modernist Fragmentation

The structure of Gerontion is highly fragmented, reflecting the instability of modern thought and experience. Eliot employs abrupt shifts in imagery, historical references, and shifting perspectives to create a sense of disorientation, forcing readers to actively piece together the poem’s meaning.

Literary Devices in Gerontion

Eliot’s use of literary techniques enhances the poem’s depth and complexity:

-

Free Verse and Irregular Meter: The poem lacks a fixed rhyme scheme or rhythm, mirroring the disjointed nature of the speaker’s thoughts.

-

Allusions: References to Shakespeare, the Bible, Greek philosophy, and historical events create layers of meaning and challenge the reader to interpret their significance.

-

Imagery: The stark and sometimes disturbing images, such as “the goat coughs at night in the field overhead,” evoke a sense of decay and unease.

-

Juxtaposition: The contrast between past greatness and present decline reinforces the theme of lost potential.

The Speaker: A Symbol of Modern Disillusionment

The old man in Gerontion is more than just an individual character; he embodies the existential crisis of the modern world. Unlike classical heroes who take decisive action, he is passive and resigned, reflecting a civilization that has lost its sense of purpose. His lamentations are not just personal regrets but a broader commentary on the failures of history and human ambition.

Gerontion in Relation to Eliot’s Other Works

The themes in Gerontion are closely connected to those in The Waste Land, which Eliot published two years later. Both poems explore spiritual desolation, historical disillusionment, and the fragmentation of modern consciousness. However, while The Waste Land presents multiple voices and perspectives, Gerontion is more intimate, focusing on a single consciousness trapped in regret and inaction.

Later in his career, Eliot’s Four Quartets (1943) would offer a more hopeful perspective on time and spirituality, but Gerontion remains one of his darkest and most unsettling works, encapsulating the despair of a generation struggling to find meaning in a broken world.

Interpretation and Critical Reception

Gerontion has been widely analyzed for its complex use of allusion and its bleak outlook on history and spirituality. Some critics view it as a critique of Western civilization’s moral failures, while others see it as a deeply personal meditation on aging and regret. Eliot himself considered Gerontion an important precursor to The Waste Land, suggesting that it contains many of the ideas that would later define his most famous work.

Here I am, an old man in a dry month,

Being read to by a boy, waiting for rain.

I was neither at the hot gates

Nor fought in the warm rain

Nor knee deep in the salt marsh, heaving a cutlass,

Bitten by flies, fought.

My house is a decayed house,

And the Jew squats on the window sill, the owner,

Spawned in some estaminet of Antwerp,

Blistered in Brussels, patched and peeled in London.

The goat coughs at night in the field overhead;

Rocks, moss, stonecrop, iron, merds.

The woman keeps the kitchen, makes tea,

Sneezes at evening, poking the peevish gutter.

I an old man,

A dull head among windy spaces.

Signs are taken for wonders. ‘We would see a sign!’

The word within a word, unable to speak a word,

Swaddled with darkness. In the juvescence of the year

Came Christ the tiger

In depraved May, dogwood and chestnut, flowering judas,

To be eaten, to be divided, to be drunk

Among whispers; by Mr. Silvero

With caressing hands, at Limoges

Who walked all night in the next room;

By Hakagawa, bowing among the Titians;

By Madame de Tornquist, in the dark room

Shifting the candles; Fräulein von Kulp

Who turned in the hall, one hand on the door. Vacant shuttles

Weave the wind. I have no ghosts,

An old man in a draughty house

Under a windy knob.

After such knowledge, what forgiveness? Think now

History has many cunning passages, contrived corridors

And issues, deceives with whispering ambitions,

Guides us by vanities. Think now

She gives when our attention is distracted

And what she gives, gives with such supple confusions

That the giving famishes the craving. Gives too late

What’s not believed in, or is still believed,

In memory only, reconsidered passion. Gives too soon

Into weak hands, what’s thought can be dispensed with

Till the refusal propagates a fear. Think

Neither fear nor courage saves us. Unnatural vices

Are fathered by our heroism. Virtues

Are forced upon us by our impudent crimes.

These tears are shaken from the wrath-bearing tree.