Seamus Heaney, a Nobel laureate in literature, is celebrated for his rich and evocative poetry that explores themes of identity, history, and human connection. Among his many works, the poem “Casualty” holds a special place, not as a traditional love poem but as a poignant meditation on loss, friendship, and the complexities of loyalty.

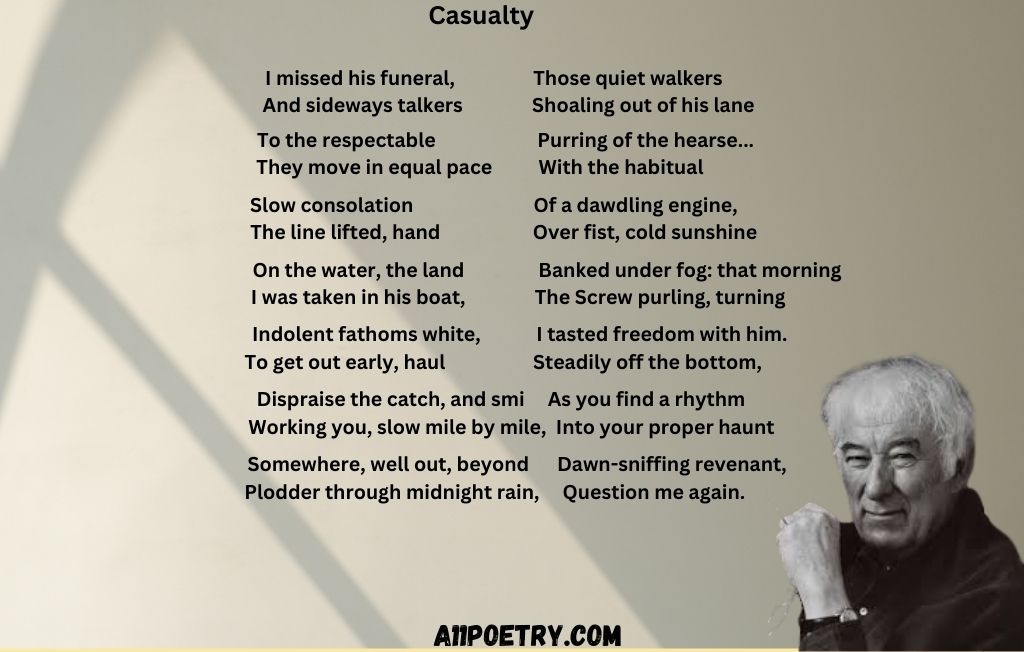

Published in Heaney’s 1979 collection Field Work, “Casualty” reflects the tumultuous political and social landscape of Northern Ireland during The Troubles, a period marked by sectarian conflict and violence. The poem focuses on the relationship between the speaker and a local fisherman, an unnamed man who becomes a victim of political strife. While the poem does not speak of romantic love, its emotional depth and exploration of personal loss can be interpreted as a profound expression of love and respect for humanity and individuality.

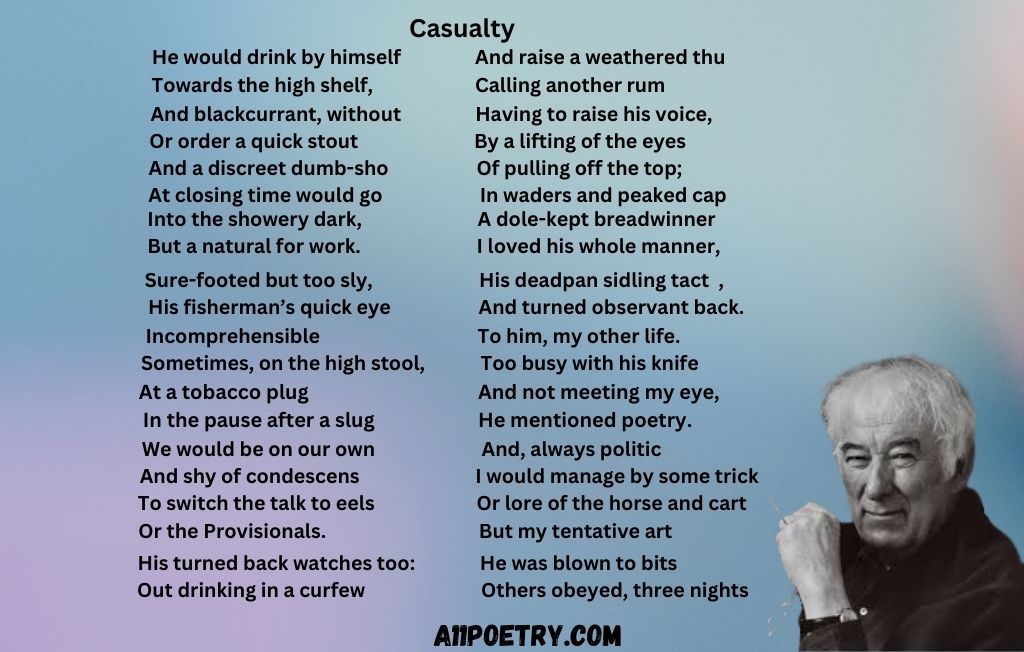

The fisherman, portrayed as a figure of quiet resilience and independence, becomes a symbol of the ordinary lives disrupted by the turmoil of the time. Heaney’s depiction of the man is intimate and compassionate, drawing attention to his habits and routines: “He would drink by himself / And raise a weathered thumb / Towards the high shelf.” These lines convey a sense of familiarity and affection, suggesting a deep connection between the speaker and the fisherman. This connection forms the emotional core of the poem, resonating as an elegy for a lost friend and a lament for the human cost of conflict.

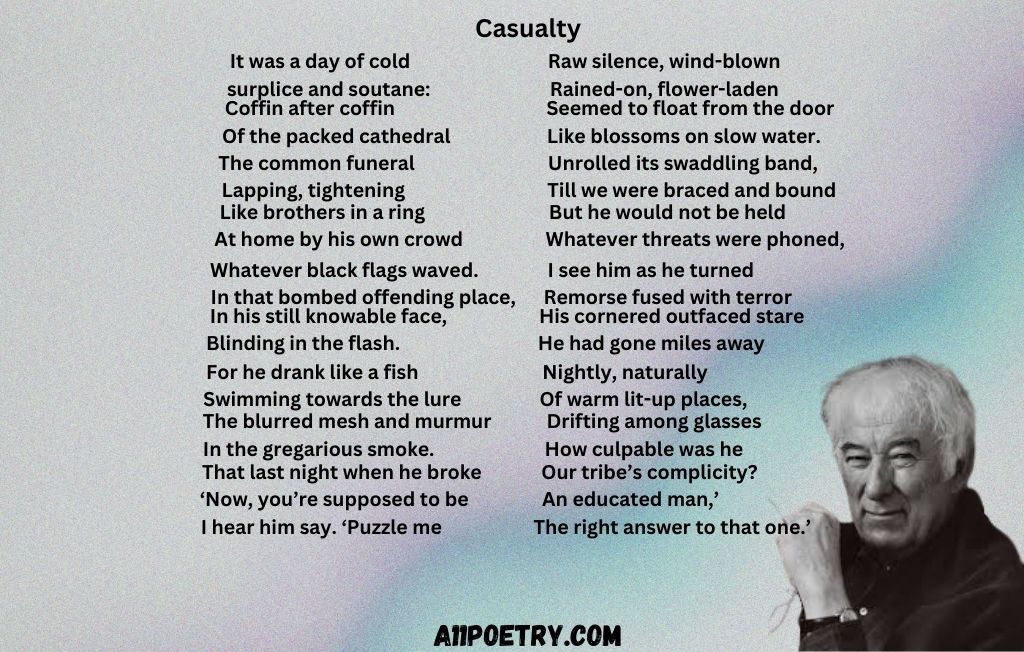

Structured in three parts, “Casualty” employs Heaney’s characteristic blend of lyrical beauty and narrative clarity. The first section paints a vivid portrait of the fisherman’s life and personality, inviting readers into a shared space of memory and camaraderie. The second section shifts to the political context, describing the aftermath of Bloody Sunday, a tragic event in 1972 when British soldiers killed 13 unarmed civilians during a protest march in Derry. The fisherman’s death, a consequence of defying a curfew to visit the local pub, becomes a microcosm of the broader conflict, highlighting the intersection of personal choice and collective suffering.

In the final section, Heaney reflects on his own role as a poet and observer. The speaker’s contemplation of the fisherman’s fate reveals a tension between loyalty to the community and a more universal empathy. This duality is encapsulated in the lines: “But my tentative art / His turned back watches too; / He was blown to bits,” where the speaker grapples with the burden of bearing witness to such tragedies.

“Casualty” is a testament to Heaney’s ability to weave personal and political threads into a cohesive and moving narrative. While not a love poem in the conventional sense, it exemplifies a form of love rooted in empathy, remembrance, and the celebration of individuality. The poem’s enduring power lies in its capacity to transcend the specifics of its historical context, offering a timeless reflection on the human condition.

Through its elegiac tone and richly textured imagery, “Casualty” invites readers to consider the fragility of life and the profound impact of love and loss. In doing so, it affirms Seamus Heaney’s place as one of the most compassionate and insightful poets of the 20th century.

Thankms for every other fantastic article. Whhere else could anybody get that kind

of information inn suchh a perfect approzch of writing?

I have a presentation next week, and I am at the look for

ssuch information. http://boyarka-inform.com/