Seamus Heaney, one of the most celebrated poets of the 20th century, is revered for his ability to weave personal experience with universal themes. Among his most poignant works is the sonnet sequence “Clearances,” a deeply moving tribute to his mother. While not a conventional love poem in the romantic sense, “Clearances” delves into the profound love shared between a mother and son, capturing the intimacy and complexity of familial bonds. In doing so, Heaney elevates the everyday into the realm of the extraordinary.

Background and Context of “Clearances”

“Clearances” is an eight-sonnet sequence written after the death of Heaney’s mother, Margaret Kathleen Heaney. Published in his 1987 collection The Haw Lantern, the sequence serves as an elegy and a reflection on their relationship. The title, “Clearances,” refers to moments of emotional clarity, as well as the physical clearing of space – a theme Heaney uses to explore both loss and connection.

While the sequence touches on grief, it is also filled with tender recollections of shared moments that underline the deep affection between mother and son. Heaney’s characteristic use of vivid imagery and tactile language makes these recollections feel immediate and relatable.

The Intimate Love in “Clearances”

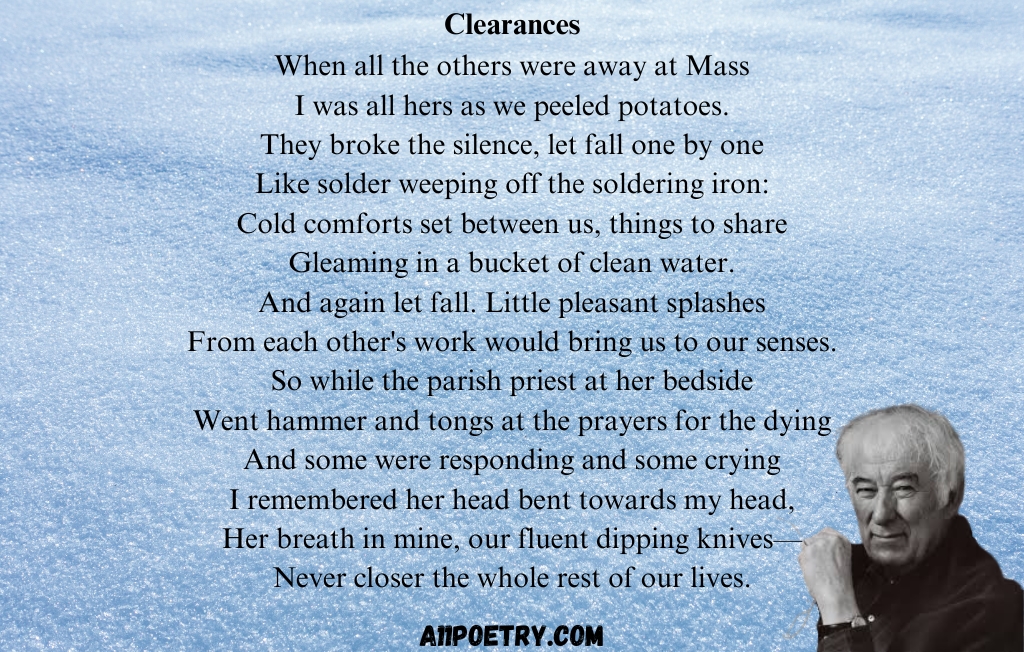

One of the most beloved sonnets in the sequence is Sonnet III, which recalls a moment of simple, shared intimacy: peeling potatoes together. The act is described with a quiet reverence:

“When all the others were away at Mass

I was all hers as we peeled potatoes.”

Here, Heaney captures the profound love in small, everyday acts. The simplicity of the scene belies its emotional depth, as the physical act of peeling potatoes becomes a metaphor for connection and togetherness. The absence of others emphasizes the exclusivity of their bond, a moment of mutual understanding and quiet companionship.

Heaney’s focus on the sensory details—the sound of the potatoes being placed into the basin, the rhythm of their work—makes the memory vivid and deeply personal. The poem suggests that love is often expressed not in grand gestures but in the unspoken, shared moments of life.

Thematic Depth and Universality

Throughout “Clearances,” Heaney explores themes of love, memory, and loss. While the sequence is a deeply personal tribute to his mother, it resonates with readers on a universal level. The relationship between parent and child is one of the most profound forms of love, marked by both intimacy and complexity. Heaney captures this beautifully in his reflections, offering insights into the enduring impact of familial love.

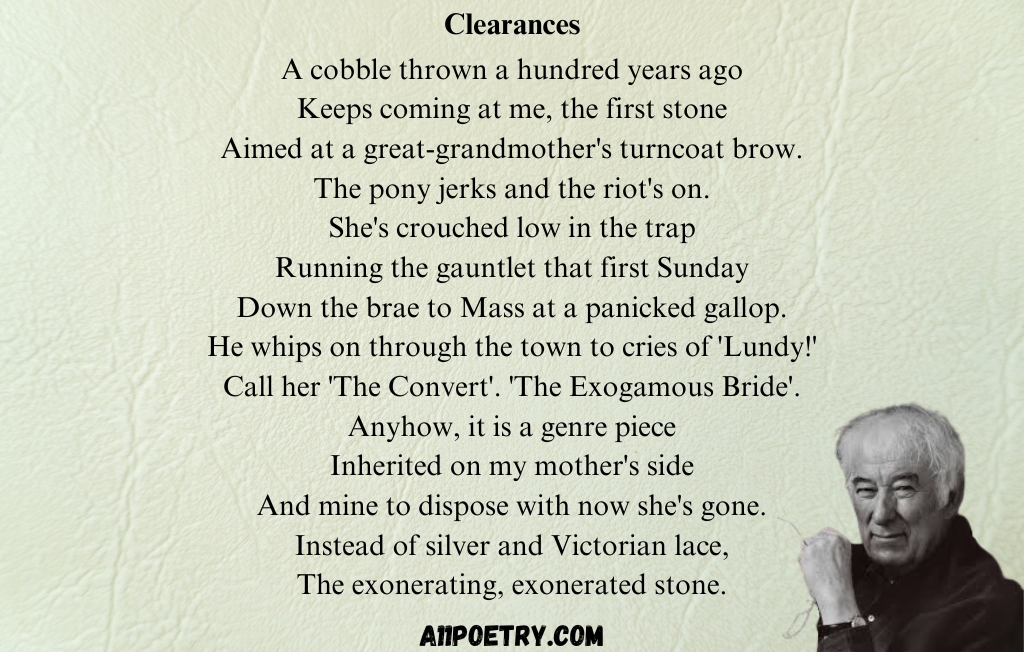

In Sonnet VII, Heaney reflects on the rituals of grief and how they connect him to his mother’s legacy:

“A cobble thrown a hundred years ago

Keeps coming at me, the first stone

In a pile of stones.”

This imagery evokes the weight of history and heritage, as well as the way love endures through time and memory. Even in death, Heaney’s connection to his mother remains a cornerstone of his identity.

A Love Poem Beyond Romance

What sets “Clearances” apart as one of Heaney’s best love poems is its ability to expand the definition of love. While traditional love poems often focus on romantic relationships, Heaney’s work highlights the equally profound love within families. This maternal love, rooted in shared history and simple acts of care, is just as worthy of poetic celebration.

The sequence also demonstrates Heaney’s mastery of the sonnet form. Each poem balances structure with emotional immediacy, using precise language to evoke a wide range of feelings. Whether recounting a memory or reflecting on loss, Heaney’s words are imbued with tenderness and sincerity.

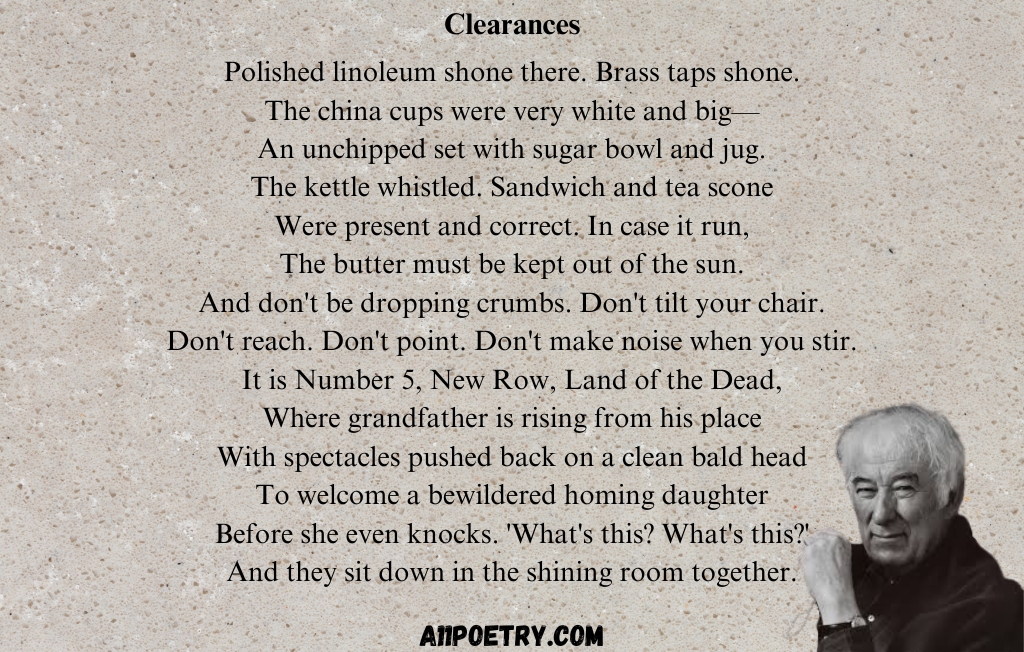

Polished linoleum shone there. Brass taps shone.

The china cups were very white and big—

An unchipped set with sugar bowl and jug.

The kettle whistled. Sandwich and tea scone

Were present and correct. In case it run,

The butter must be kept out of the sun.

And don’t be dropping crumbs. Don’t tilt your chair.

Don’t reach. Don’t point. Don’t make noise when you stir.

It is Number 5, New Row, Land of the Dead,

Where grandfather is rising from his place

With spectacles pushed back on a clean bald head

To welcome a bewildered homing daughter

Before she even knocks. ‘What’s this? What’s this?’

And they sit down in the shining room together.

When all the others were away at Mass

I was all hers as we peeled potatoes.

They broke the silence, let fall one by one

Like solder weeping off the soldering iron:

Cold comforts set between us, things to share

Gleaming in a bucket of clean water.

And again let fall. Little pleasant splashes

From each other’s work would bring us to our senses.

So while the parish priest at her bedside

Went hammer and tongs at the prayers for the dying

And some were responding and some crying

I remembered her head bent towards my head,

Her breath in mine, our fluent dipping knives—

Never closer the whole rest of our lives.

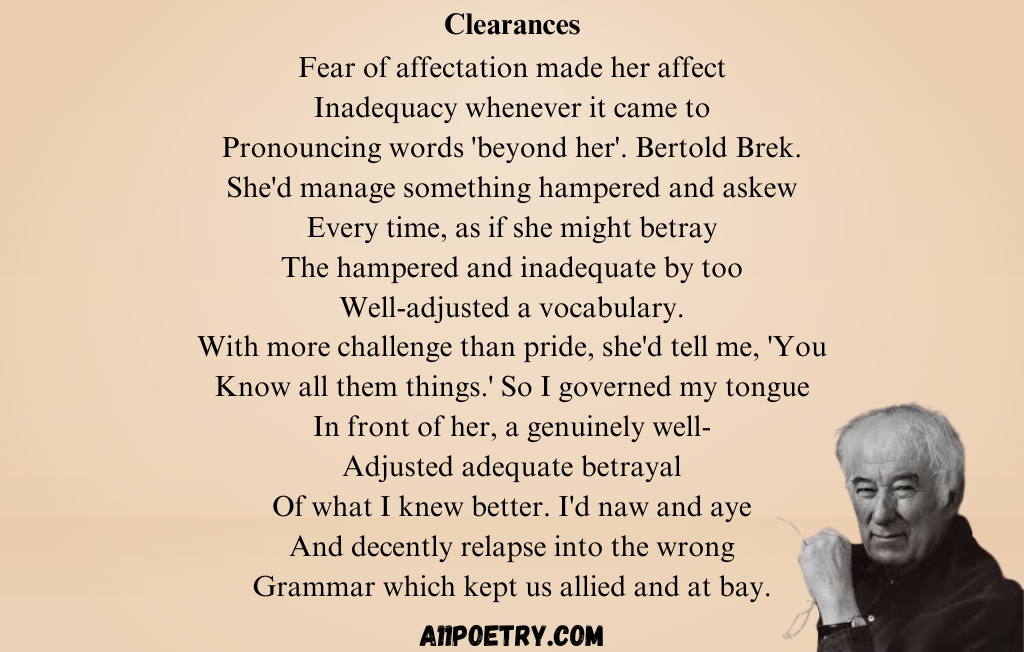

Fear of affectation made her affect

Inadequacy whenever it came to

Pronouncing words ‘beyond her’. Bertold Brek.

She’d manage something hampered and askew

Every time, as if she might betray

The hampered and inadequate by too

Well-adjusted a vocabulary.

With more challenge than pride, she’d tell me, ‘You

Know all them things.’ So I governed my tongue

In front of her, a genuinely well-

Adjusted adequate betrayal

Of what I knew better. I’d naw and aye

And decently relapse into the wrong

Grammar which kept us allied and at bay.

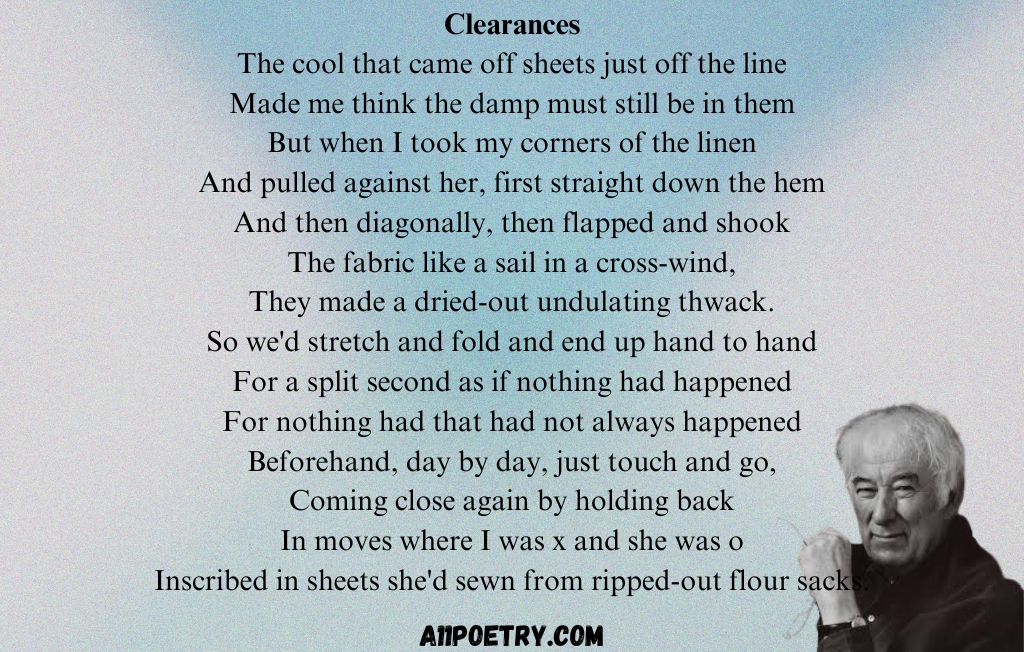

The cool that came off sheets just off the line

Made me think the damp must still be in them

But when I took my corners of the linen

And pulled against her, first straight down the hem

And then diagonally, then flapped and shook

The fabric like a sail in a cross-wind,

They made a dried-out undulating thwack.

So we’d stretch and fold and end up hand to hand

For a split second as if nothing had happened

For nothing had that had not always happened

Beforehand, day by day, just touch and go,

Coming close again by holding back

In moves where I was x and she was o

Inscribed in sheets she’d sewn from ripped-out flour sacks.

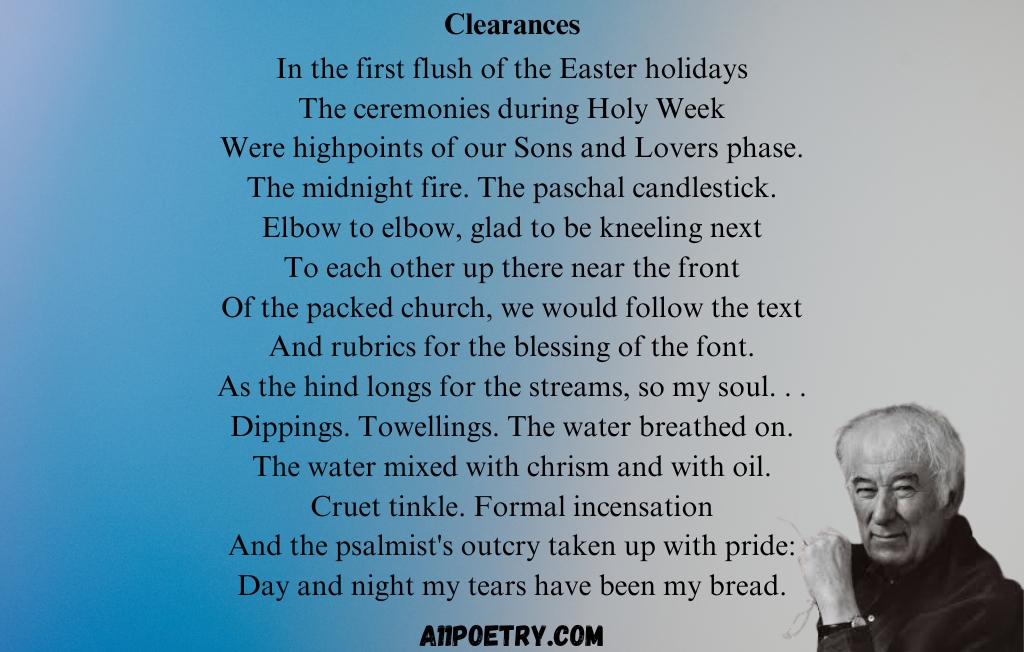

In the first flush of the Easter holidays

The ceremonies during Holy Week

Were highpoints of our Sons and Lovers phase.

The midnight fire. The paschal candlestick.

Elbow to elbow, glad to be kneeling next

To each other up there near the front

Of the packed church, we would follow the text

And rubrics for the blessing of the font.

As the hind longs for the streams, so my soul. . .

Dippings. Towellings. The water breathed on.

The water mixed with chrism and with oil.

Cruet tinkle. Formal incensation

And the psalmist’s outcry taken up with pride:

Day and night my tears have been my bread.

In the last minutes he said more to her

Almost than in all their life together.

‘You’ll be in New Row on Monday night

And I’ll come up for you and you’ll be glad

When I walk in the door . . . Isn’t that right?’

His head was bent down to her propped-up head.

She could not hear but we were overjoyed.

He called her good and girl. Then she was dead,

The searching for a pulsebeat was abandoned

And we all knew one thing by being there.

The space we stood around had been emptied

Into us to keep, it penetrated

Clearances that suddenly stood open.

High cries were felled and a pure change happened.

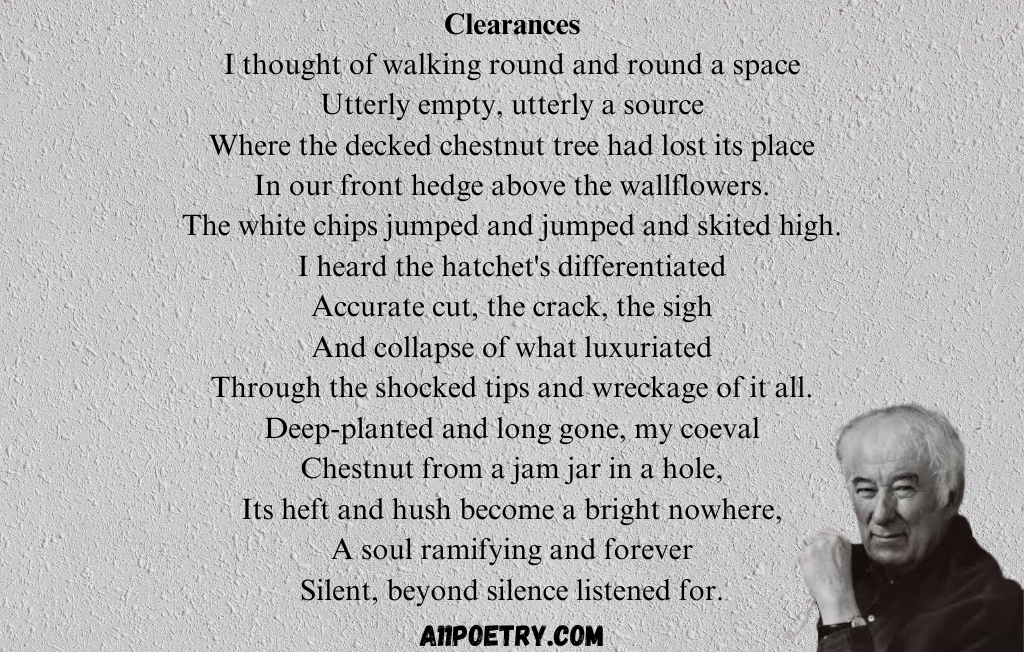

I thought of walking round and round a space

Utterly empty, utterly a source

Where the decked chestnut tree had lost its place

In our front hedge above the wallflowers.

The white chips jumped and jumped and skited high.

I heard the hatchet’s differentiated

Accurate cut, the crack, the sigh

And collapse of what luxuriated

Through the shocked tips and wreckage of it all.

Deep-planted and long gone, my coeval

Chestnut from a jam jar in a hole,

Its heft and hush become a bright nowhere,

A soul ramifying and forever

Silent, beyond silence listened for.

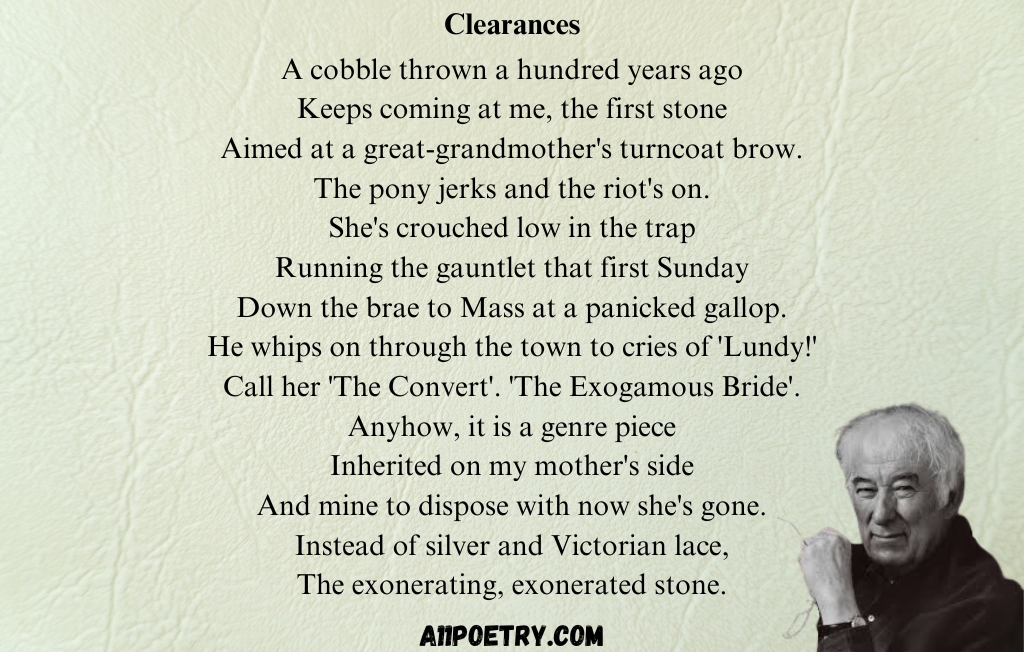

A cobble thrown a hundred years ago

Keeps coming at me, the first stone

Aimed at a great-grandmother’s turncoat brow.

The pony jerks and the riot’s on.

She’s crouched low in the trap

Running the gauntlet that first Sunday

Down the brae to Mass at a panicked gallop.

He whips on through the town to cries of ‘Lundy!’

Call her ‘The Convert’. ‘The Exogamous Bride’.

Anyhow, it is a genre piece

Inherited on my mother’s side

And mine to dispose with now she’s gone.

Instead of silver and Victorian lace,

The exonerating, exonerated stone.