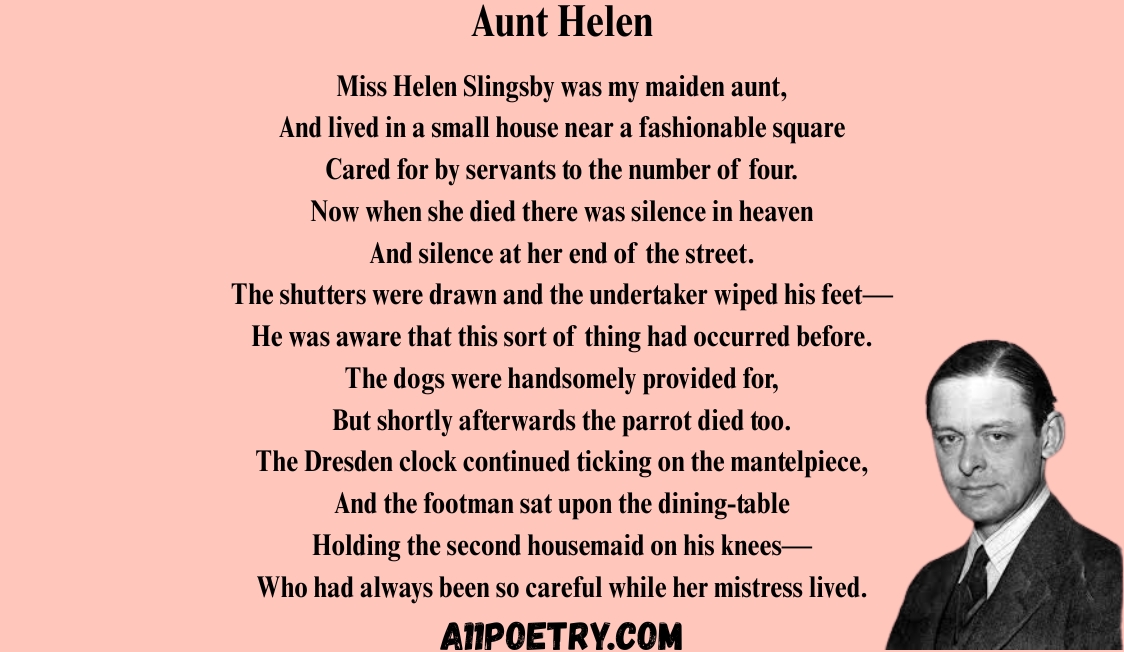

T.S. Eliot’s early love poem Aunt Helen, part of his 1917 collection Prufrock and Other Observations, presents a brief, ironic portrait of a deceased upper-class woman and the absurdities of mourning rituals within a decaying social class. Though often overlooked compared to Eliot’s longer, more complex poems like The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock or The Waste Land, Aunt Helen demonstrates many of the characteristics for which Eliot became renowned: sharp irony, economical language, and a concern with spiritual and cultural decline.

At only twelve lines, Aunt Helen is deceptively simple, using a narrative tone that borders on the satirical. The poem describes the death of a wealthy woman, Aunt Helen, and the aftermath of her passing. While the details are few, Eliot imbues each line with nuance, layering mockery over genuine melancholy, and exposing the hollowness of formal mourning.

On the surface, the poem offers a short obituary-like summary: Aunt Helen dies, her house is quiet, her pets are affected, and the staff misbehave in her absence. But Eliot’s phrasing transforms what could be a sentimental remembrance into an ironic critique. He establishes a tone of quiet detachment and mild cynicism, highlighting the artificiality and futility of upper-class life and its rituals.

The opening line, “Miss Helen Slingsby was my maiden aunt,” is a matter-of-fact introduction. The specificity of the name and relationship—”maiden aunt”—immediately evokes a certain type of woman, unmarried and childless, living out her life in genteel obscurity. The setting—a “small house near a fashionable square”—is also important, as it emphasizes proximity to wealth and prestige, rather than full membership in that world.

Eliot uses a subtle shift in diction to insert dry humor and irony. The image of the undertaker wiping his feet, for instance, is both literal and symbolic. On one hand, it shows respect for the decorum of the household; on the other, it comically suggests how routine such deaths are—”he was aware that this sort of thing had occurred before.” This line, delivered with deadpan irony, undercuts the gravity of death with a tone of weary familiarity, implying that Aunt Helen’s death is entirely unremarkable.

The next lines continue this tone, describing how the pets are handled—“The dogs were handsomely provided for, / But shortly afterwards the parrot died too.” These lines may initially seem trivial, but they actually reinforce the poem’s critique of performative mourning and material legacy. The fact that the dogs are “handsomely provided for” says more about the priorities of the household and its class than about the emotional weight of the death. The parrot’s death, presumably from neglect or loneliness, adds a darkly comic twist—death triggers a breakdown in the artificial ecosystem of the household.

The final lines escalate the satire. “The Dresden clock continued ticking on the mantelpiece,” evokes the idea of time’s indifference to human death. But this too is a symbol: a delicate, imported clock, likely a family heirloom, continues its rhythm as if nothing has changed. It’s a powerful metaphor for the unfeeling march of time and the hollow continuity of bourgeois existence.

The poem ends with a brief image of chaos and transgression: the footman sitting on the dining table with the second housemaid on his lap. This sudden eruption of sensuality and rebellion contrasts sharply with the preceding propriety. The phrase “who had always been so careful while her mistress lived” underlines the repression under Aunt Helen’s rule. Her death, therefore, not only signifies personal loss but also the release of repressed human instincts previously subdued by social decorum.

Eliot’s Aunt Helen is therefore both a satire and a subtle elegy. It mocks the emptiness of upper-class rituals, the mechanical continuance of objects after death, and the suppression of natural human desires. At the same time, there’s an underlying sadness—not at Aunt Helen’s passing, but at the artificial, emotionally stunted world she inhabited. This duality is a hallmark of Eliot’s early poetry, in which he deftly balances detachment with underlying emotion, irony with insight.

The poem also anticipates Eliot’s broader concerns with modernity, alienation, and the fragmentation of meaning. Though brief and relatively light compared to his major works, Aunt Helen offers a microcosm of Eliot’s poetic vision: a world where tradition has decayed into formality, where people act out roles with little spiritual conviction, and where death reveals not just the end of life but the emptiness of what preceded it.

In this way, Aunt Helen remains a pointed, poignant, and darkly humorous exploration of class, death, and the absurdity of social conventions—hallmarks of T.S. Eliot’s enduring literary legacy.